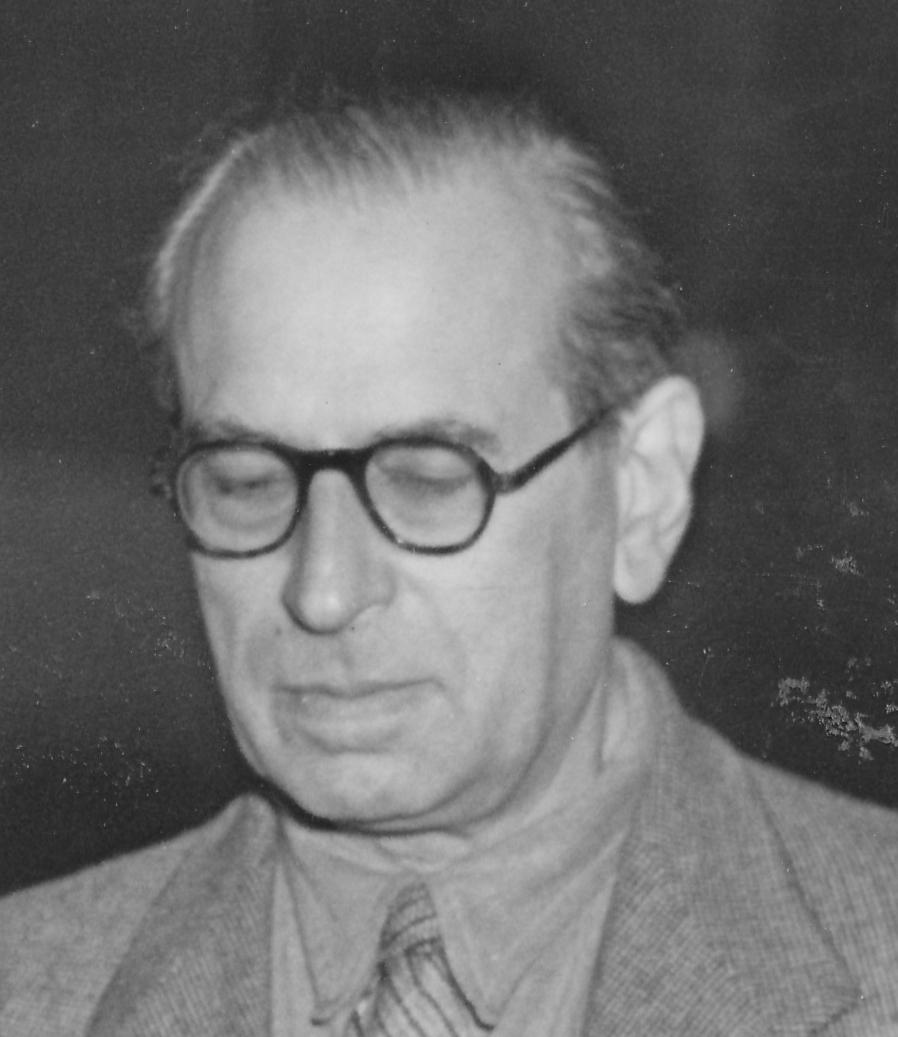

Book review by John Foley: Originally published in British Chess News, 27 May 2024

I have a parochial interest in any book on Reginald Pryce Michell because he ended his playing career as a member of Kingston Chess Club of which I have the privilege to be president. His main career was in the first third of the 20th century. Other notable contemporary club members from the 1930s include the legendary Pakistani player Mir Sultan Khan, the chess author Edward Guthlac Sergeant and Joseph Henry Blake against whom we show some Michell games below.

Following this book review, we obtained the curated game collection of R. P. Michell from John Saunders of Britbase.

Updated and expanded edition

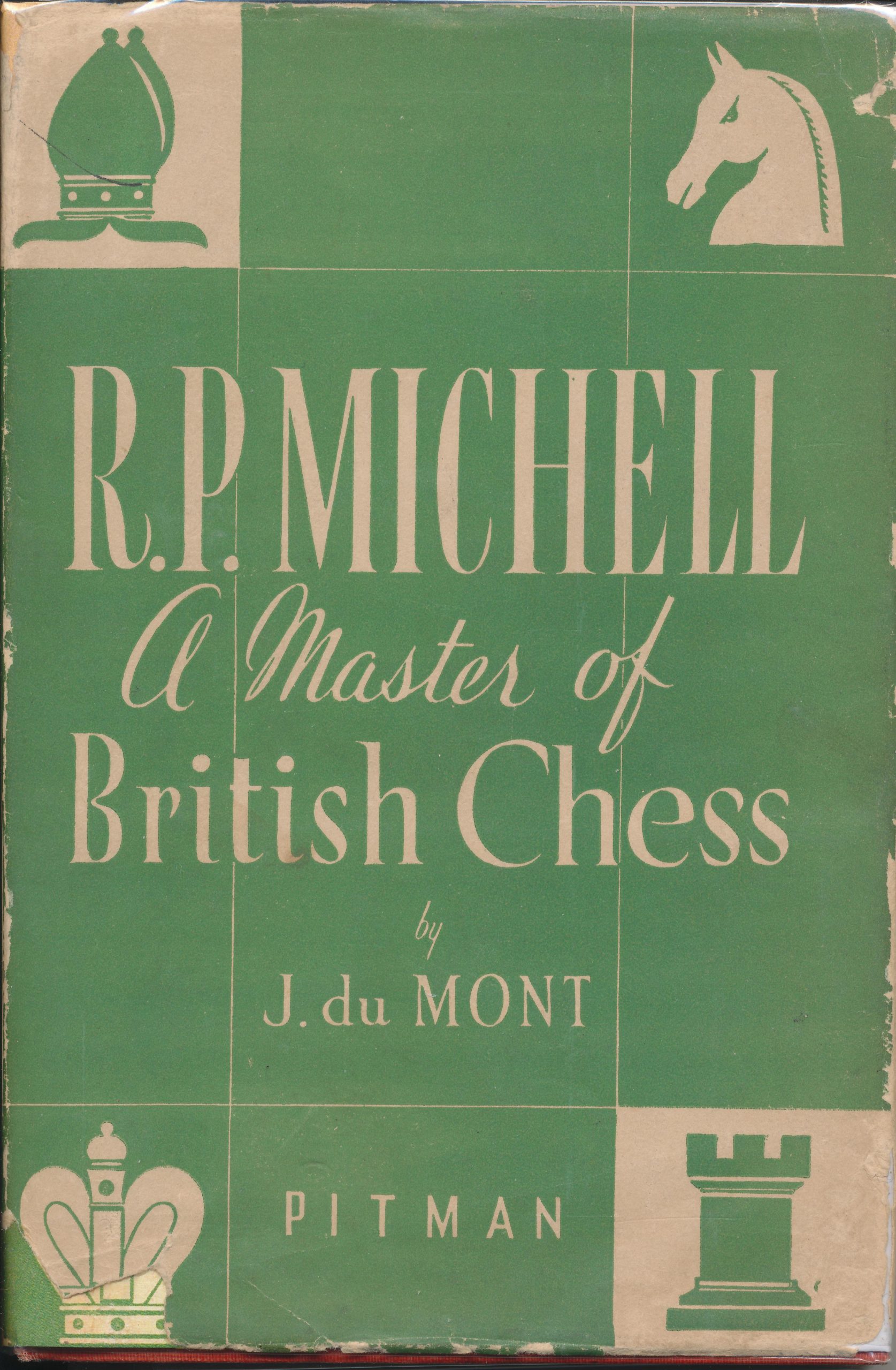

This new book from Carsten Hansen is a welcome addition to the coverage of an important player who represented England. It is an update and expansion of the book originally published in 1947 by Pitman, London and compiled by Julius du Mont, the former editor of British Chess Magazine.

The original book has long been out of print, so the new book allows players to familiarise themselves with an almost forgotten former luminary of English chess.

Reginald Pryce Michell

I share some background on R. P. Michell from my article on the history of Kingston Chess Club.

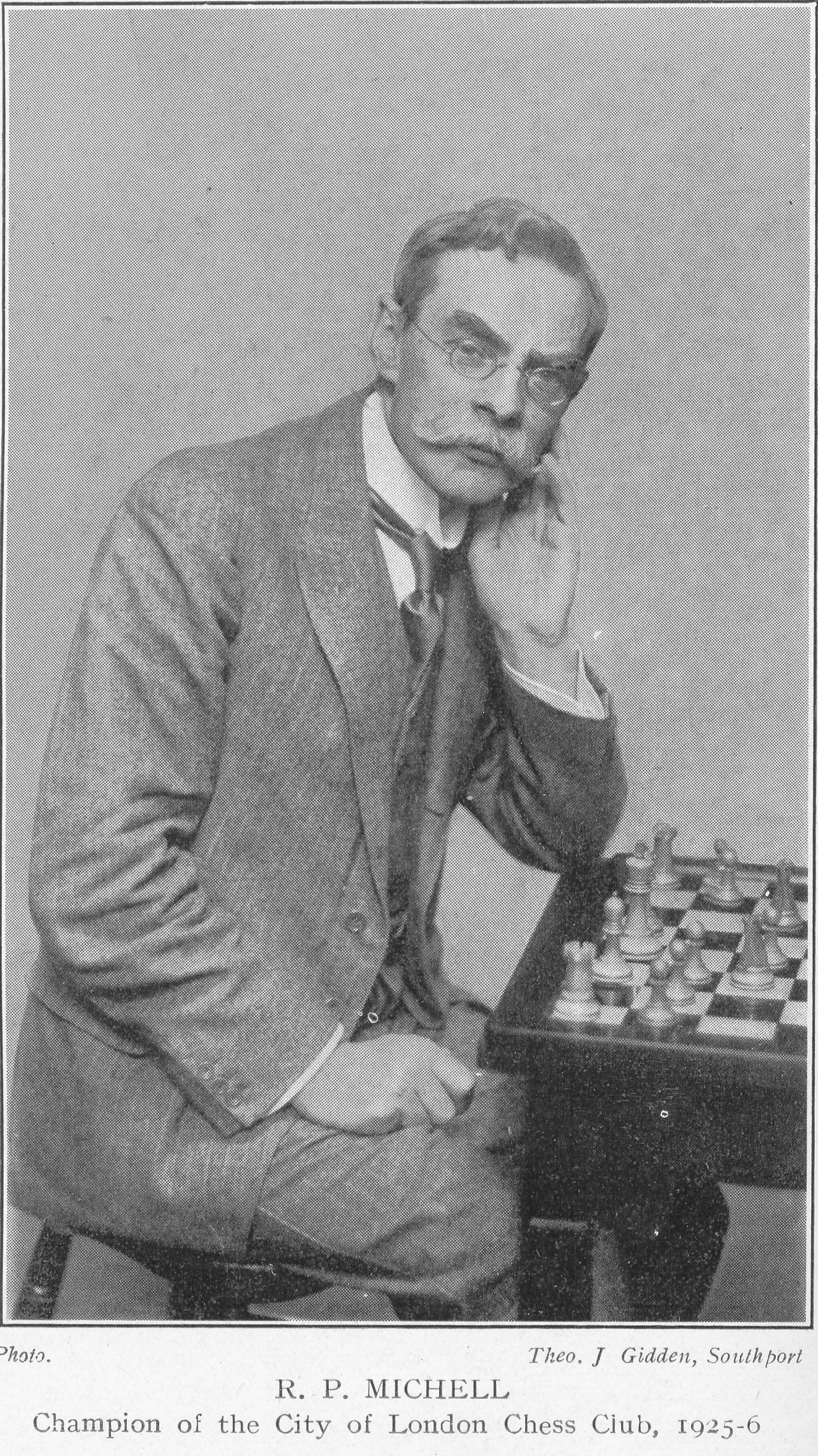

photographer: Theo J. Gidden, Southport

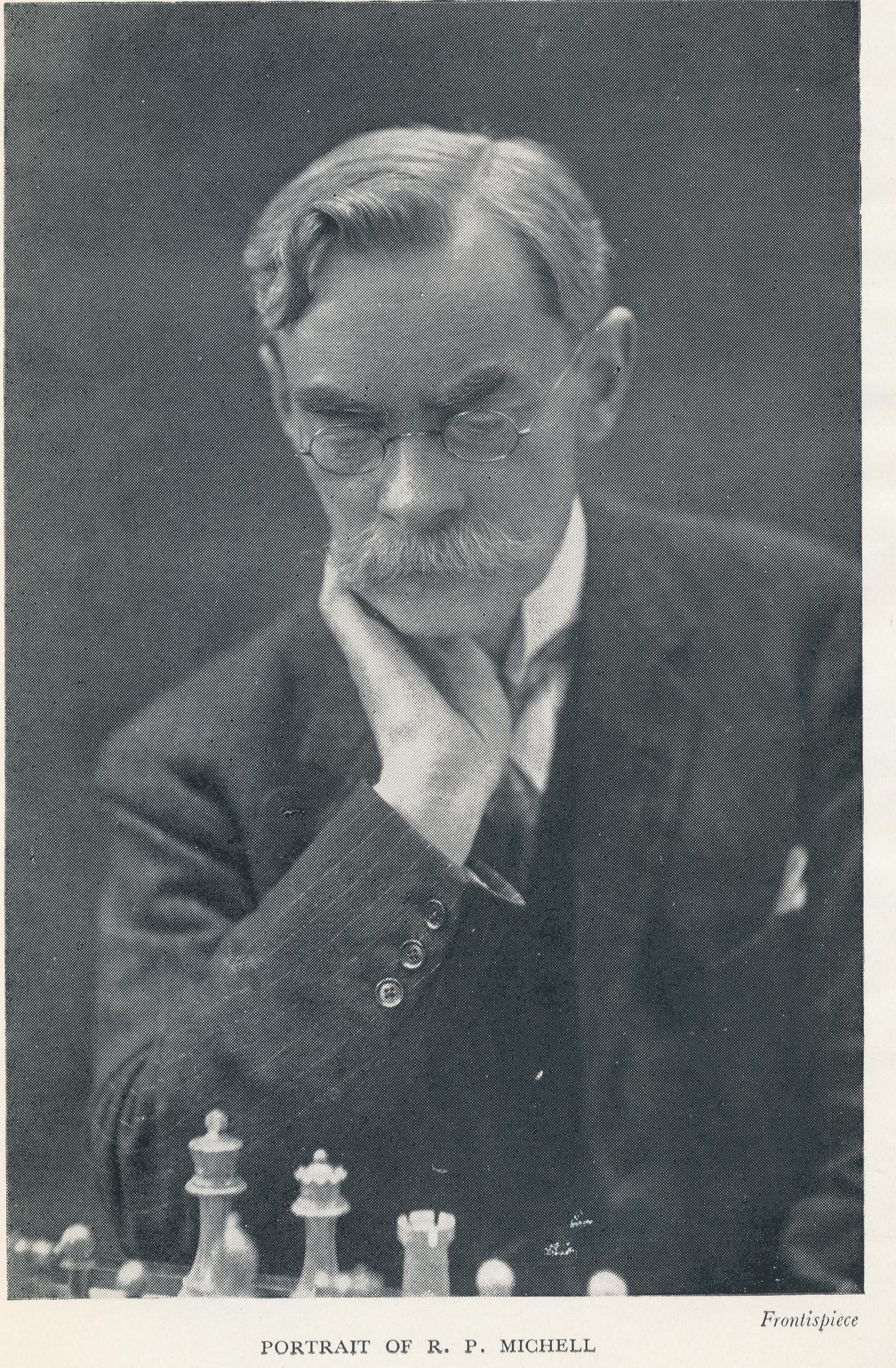

Michell (1873-1938) was the British amateur chess champion in 1902 and played for Great Britain in the inaugural 1927 Olympiad in London and the 1933 Olympiad in Folkestone. He played in eight England v USA cable matches between 1901 and 1911. He participated in the Hastings Premier over 20 years, defeating both Sultan Khan and Vera Menchik in 1932/33. He finished second, third and fourth in the British championship (officially constituted in 1904), beating the multiple champion H.E. Atkins on several occasions. Modern estimates have placed him at the level of a strong international master.

Michell’s track record is all the more remarkable because he worked in a senior position at the Admiralty throughout his career which left him little time to study chess theory or enter competitions. He had a “wide knowledge of English and French literature, and a book of essays in either language was his standby for any unoccupied moment.” He died aged 65 which was the official retirement age at that time.

Michell excelled in the middle game and could hold his own in the endgame as attested by his draws against endgame maestros Capablanca and Rubinstein. In the only article he ever wrote about chess, he singled out books on the endgame as the most useful for practical purposes.

E.G. Sergeant wrote of him: “Michell’s courtesy as a chess opponent was proverbial, and on the rare occasions when he lost he always took as much interest in playing the game over afterwards as when he had won, and never made excuses for losing. Of all my opponents, surely he was the most imperturbable. Onlookers might chatter, whisper, fall off chairs, make a noise of any kind, and it seemed not to disturb him; even when short of time, he just sat with his hands between his knees, thinking, thinking.”

Michell’s wife Edith (maiden name Edith Mary Ann Tapsell) was British women’s champion in 1931 (jointly), 1932 and 1935, and played alongside him for Kingston & Thames Valley chess club.

A Master of British Chess – what’s new?

The original book covered 36 games; the new book has been expanded considerably to 67 games. Moreover, the additional games are against some of the most notable players of the era, including several world champions. Chess historians should be grateful for the revival of the original game selection, which du Mont described as “characteristic games”, by the addition of another 31 “notable games”.

Self-published books are a labour of love because the subject lacks the mileage to justify the attention of a conventional publisher. The author lacks the quality assurance tasks typically carried out by a publisher such as proofreading and fact-checking. This is apparent in the first part of the book which reproduces the text from the original, presumably using a scanner which hiccoughed over some obscure passages. The spelling has been converted to American, which grates for a book on a quintessentially English player.

A frustrating omission in the new book is a list of games to navigate the collection; the original book contained a list showing game numbers, players, event locations and dates. In mitigation, the new book does have a useful index of openings and ECO codes as well as an index of opponents. Hansen claims that the first book had 37 games whereas it had 36. Perhaps we can take comfort that later Amazon printings will correct these infelicities.

The new book has some significant improvements over the original. As one might expect, the moves are now in algebraic rather than the descriptive format with which most players under 50 are now unfamiliar. In the text, whilst d-pawn is the modern equivalent of the queen’s pawn, I still hanker after naming the pawn according to the name of the file; it would be a comforting continuity with descriptive notation. The openings are given their modern names with ECO classifications. Casual readers will appreciate the increased number of diagrams accompanying each game. For example, for the game Blake v Michell, Caterham 1926, the original book only had one diagram compared to a generous five for the new book. Many of the original games did not appear in any commercial database. No doubt this situation will be remedied in short order.

The most frequent opponents listed in the revised book include his strong English contemporaries: Sir George Thomas, William Winter and Fred Yates with four games apiece. Hansen added notable opponents who should have been included in the first book on account of their elevated status in the chess world, including five world champions: Alekhine, Botvinnik, Capablanca (two games), Euwe, Menchik (woman world champion) as well as Maroczy, Marshall, Rubinstein and Sultan Khan who were posthumously recognised as grandmasters.

The edited first part

The first part of the book carries the concise game summaries of the original, which were proofread by the precocious Leonard Barden whilst still at Whitgift School who lived a short cycle ride from du Mont in Thornton Heath. The book came out a year later in 1947 when Barden started his National Service.

The editor of Chess Magazine, Baruch Wood, was scathing in his book review: “Britain is far from the top of the chess tree and there must be a hundred British players with better justification for the publication of a book of their games than Michell. Mr du Mont’s graceful pen has made the most of his subject. The price of the book (10/6 for 108pp, 36 games) is so extraordinarily high that one feels some appeal is being made to sentiment.”

No doubt the fact that du Mont was the editor of a rival magazine may have diluted Wood’s objectivity. England did not have a surfeit of players and Michell would have been in the first rank.

Hansen has added his comments as italicised notes in the text in the contemporary, rather dry style redolent of engine and database analysis. Inevitably, he has identified some improvements and errors which were not noticed in the original. These include not only outright blunders but also the missed opportunities. The logic of this approach is harsh and sits somewhat uncomfortably with the convention that the chess public is more forgiving of a failure to play the best move than of making a blunder. Treating both these types of inaccuracy symmetrically makes the world feel less tolerant.

Misattribution

The most significant discovery by Hansen is that one of the games (game 27) had been misattributed regarding who played White. Du Mont had Michell defeating Max Euwe (world champion 1935-37) at Hastings 1931, whereas Michell had lost.

Hansen surmises that the game intended for the collection was the game they played in the following year’s Hastings tournament when Michell had Euwe on the ropes but the game ended in a draw. We don’t know exactly how this error occurred, but confusion sometimes arises when quoting games at Hastings. This famous long-running annual tournament traditionally takes place in the period between Christmas and the New Year and is described according to the year it starts and the year it ends. Michell lost the game played in 1930/31, but drew the game they played in 1931/32.

Biography untouched

Carsten Hansen is a chess analyst rather than a professional biographer so it is perhaps wise that he has not attempted to update the biographical sketch provided by Du Mont. When the chess analyst Daniel King wrote a book on Sultan Khan, he got into hot water regarding his contested account of the life of the grandmaster.

Modern analysis compared

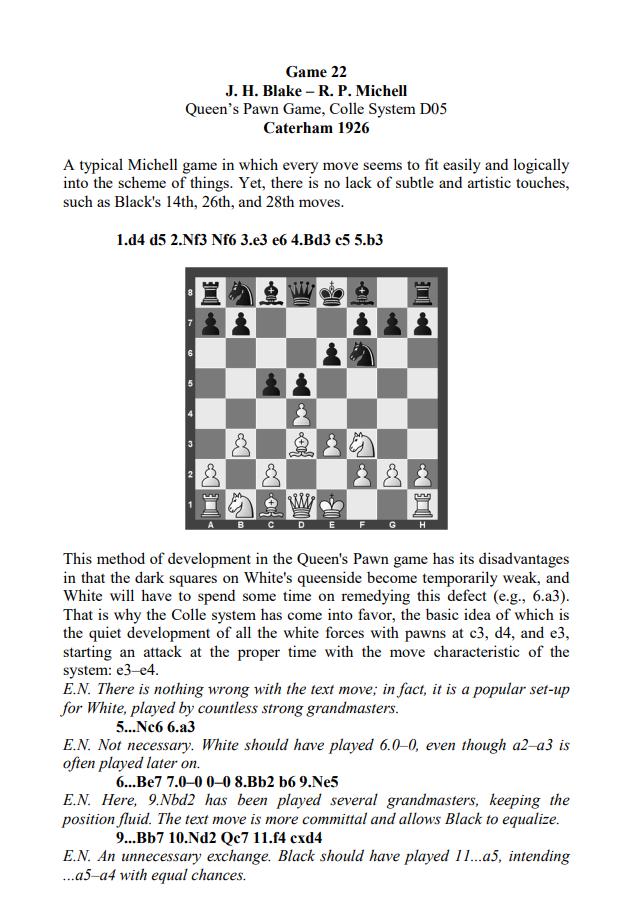

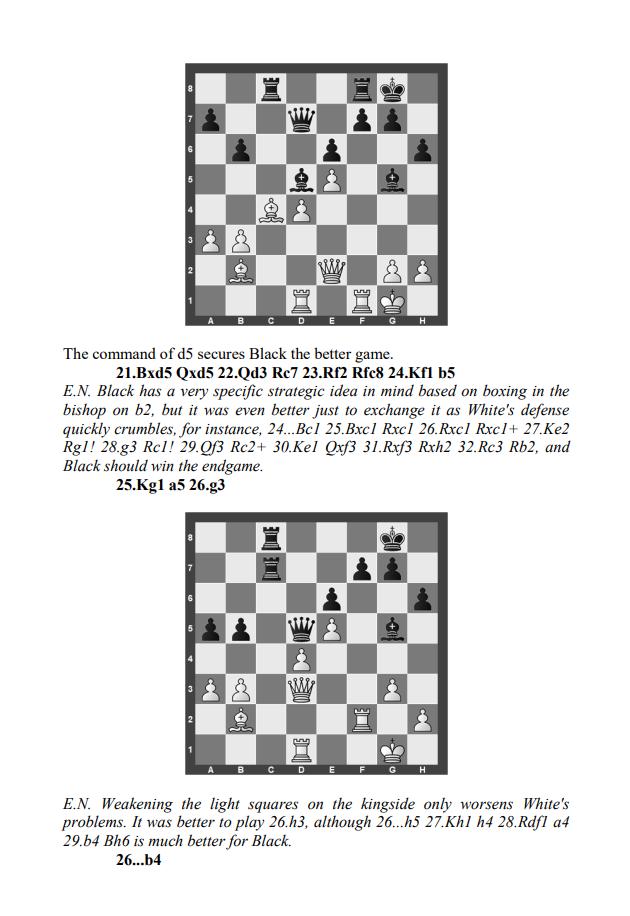

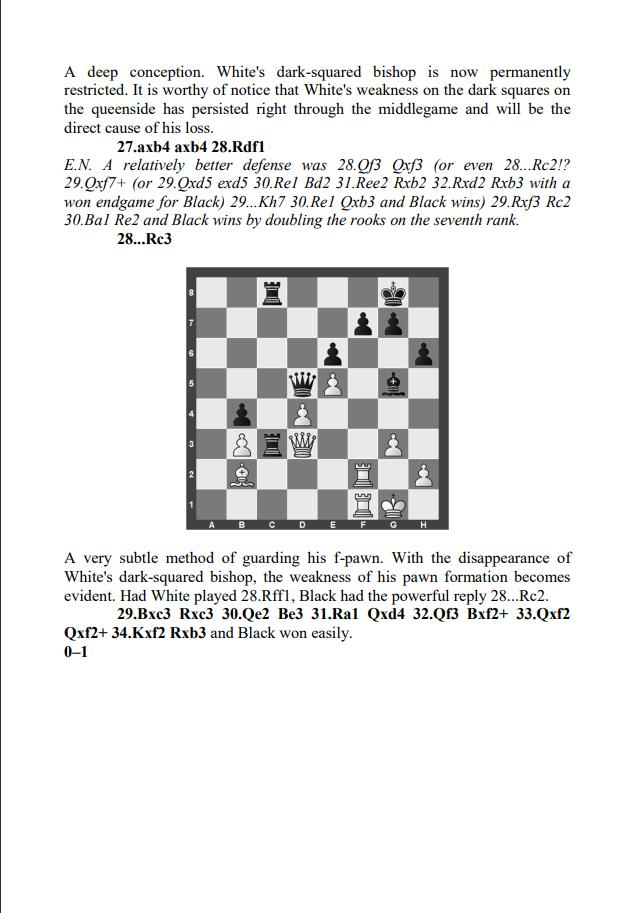

We may compare annotations between the original and the revised version of the book regarding the above-mentioned game. Here we have (courtesy of CH) an excerpt of the new book on the game Blake v Michell, Caterham, 1926. Blake, although half a generation older than Michell, was described by Du Mont as “one of the brilliant band of British amateurs of which R. P. Michell was one.”

and

and

and finally

We may briefly examine the new analysis. The original text by Du Mont/Barden criticises Blake’s choice of opening: “This method of development in the Queen’s Pawn game has its disadvantages in that the dark squares on White’s queenside become temporarily weak, and White will have to spend some time on remedying this defect (e.g., 6.a3). That is why the Colle system has come into favour, the basic idea of which is the quiet development of all the white forces with pawns at c3, d4, and e3, starting an attack at the proper time with the move characteristic of the system: e3-e4.”

Hansen gives short shrift to this perspective:

“There is nothing wrong with the text move; in fact, it is a popular set-up for White, played by countless strong grandmasters.”

This blunt contradiction is based upon a century of games played thereafter. However, the original comment may have seemed plausible in the era in which Colle popularised the system and it had yet to be fully proven.

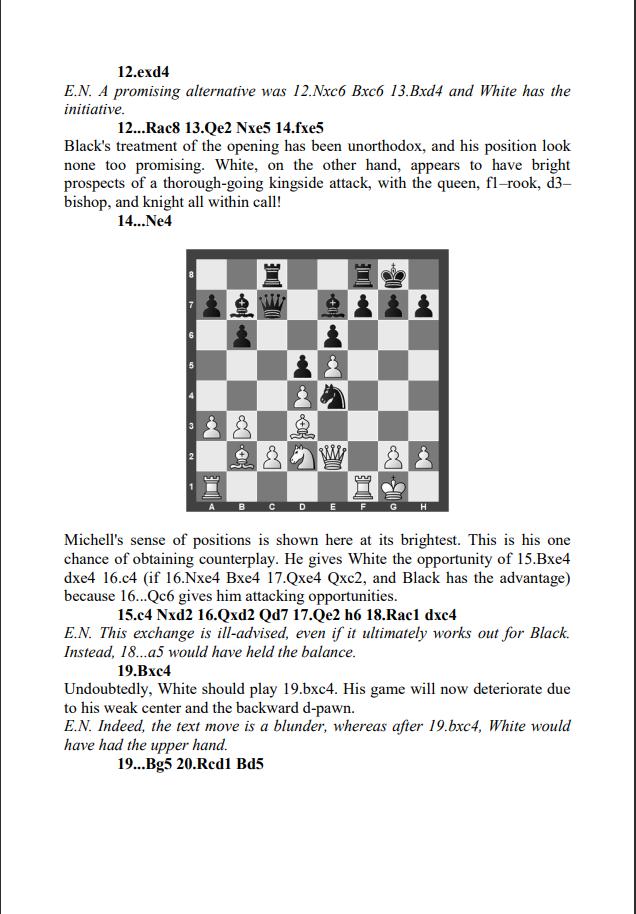

After Black’s 18th move (diagram above), the original annotation prefers an alternative to the move played 19. Bxc4: “Undoubtedly, White should play 19. bxc4. His game will now deteriorate due to this weak centre and the backward d-pawn.”

Hansen is again blunt:

“Indeed, the text move is a blunder, whereas after 19. bxc4, White would have had the upper hand.”

According to Deep Hiarcs (running for one minute), the difference in evaluation between 19. bxc4 and 19. Bxc4 is the difference between +0.2 and -0.3. So at worst, this “blunder” puts Blake a third of a pawn behind instead of being a fifth of a pawn ahead. Whilst masters thrive on small measures, it seems an exaggeration to describe capture by the bishop as a blunder. The original narrative merely says that the pawn capture would have been preferable without overstating the difference. Perhaps there is a tendency when aided by an engine to lose sight of the natural uncertainties felt by chess players when ruminating on which piece to recapture with.

Drama at Hastings 1934-35

The foreword to the original book noted that the most dramatic moment of Michell’s career occurred at the annual Hastings Premier 1934-35. He was pitted in the last round against Sir George Thomas, who was then half a point ahead of Dr Euwe, having beaten Capablanca and Botvinnik. Some observers felt that the decent and patriotic course of action was to give Sir George an easy game.

As one later commentator remarked, “In almost any other country, at any other time, the result would have been foreordained: a friendly draw and Thomas finishes no worse than a tie for first. Indeed, many players had to be rooting for the universally beloved Thomas to win and come in sole first.”

There had not been a home winner since Henry Ernest Atkins in 1921, the first year the annual tournament was held. Thomas and Michell were England team-mates. However, Thomas slipped up and Michell pressed home his advantage. Thomas lost the game but tied for first place with Euwe and Flohr. Curiously, the original book did not include this crucial game. Hansen includes the game and praises Michell for his principled stance: “But there was a happy ending; Max Euwe, in a better position against tail-ender Norman, made a sporting gesture of his own by offering a draw unnecessarily and settling for a first-place tie with Thomas and Flohr.”

The second part

Hansen annotates the games in the new second part of the book in a readable style and does not let Stockfish intrude too much. He even offers his thoughts on some moves rather than taking the engine recommendations. The prose is functional: the game introductions lack the charm of the original game summaries. Whilst sometimes providing background information on the opponent, there is little attempt in the header to identify the key points from each game.

Hansen is consistent with the narrative style in the first part by avoiding long algebraic variations. Even if his move criticisms are sometimes anachronistic, he has been considerate in generally referring to older games when citing continuations. It must have been tempting to refer to games played in the database era.

The original book held to the hagiographic compiler’s conceit of not showing any losses save for the aforementioned misattribution. The reader would perhaps have gained more of an understanding of the subject’s character if presented with some games in which he struggled or indeed blundered. For example, Michell was crushed in 21 moves by Atkins at Blackpool in 1937 when he was still in his prime, even if he died a year later.

Hansen does not resist presenting Michell’s loss to Capablanca at Hastings in the Victory Congress of 1919. It was clear even then that Capablanca would be one of the next holders of the world championship. The game’s introductory text is misleading: “You don’t often get chances to play the best players in the world, let alone take points from them, even if it is ‘just’ a draw.” The implication is that this game (No. 41) is drawn whereas it is a win for Capablanca. In total the book contains two losses, 14 draws and 51 wins for Michell.

In the majority of the games in the second part, Hansen focuses on blunders by Michell or his opponent. There is no doubt that the top players from a century ago were not as strong as the top players of today, but it seems churlish to show so many games with blunders. Comparatively few moves have been awarded an exclamation mark. Perhaps the book should have been shorter, with higher-quality games. However, on closer inspection, the “blunders” are treated in the modern sense as discussed above. They are not the traditional blunders, bad moves losing the game, that would have been described by a contemporary annotator. Rather, they are blunders in which the game evaluation has switched by a certain margin.

Michell, a follower of Nimzovich, focused on positional advantages; tactical skirmishes and sacrifices were few and far between. A slight exception to this style was found in the game Blake v Michell, Hastings, 29 December 1923:

Conclusion

R. P. Michell should be an inspiration to amateur players with a full-time career. He made a mark in the chess world using solid play, eschewing theoretical or sharp lines. He held his own against the strongest players in the world. Carsten Hansen has brought welcome attention to this forgotten English master. The new book nearly doubles the number of games covered and introduces modern engine analysis. The reader will find many examples of successful middle-game strategies. Above all, we learn that chess is a struggle: one should keep trying to improve the position and make things difficult for the opponent. I recommend this book, especially to club players looking for new chess ideas.

Kingston won the Alexander Cup, the Surrey team knockout tournament, in 1931/32 with Michell.

Book details :

- Hardcover : 318 pages

- Publisher: CarstenChess (16 Mar. 2024)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:8793812884

- ISBN-13:978-8793812888

- Product Dimensions: 15.24 x 1.83 x 22.86 cm